Does Apple care about developers?

An analysis of Apple's App Store business practices.

In the last 24 hours, the EU announced a series of anti-trust investigations into Apple's business practices, with one investigation directly auditing Apple's App Store policies. Their argument, in short, is that Apple is putting many apps and services at a disadvantage by directly competing with them on the App Store, while keeping a 15-30% cut. Apple has long argued that the development tools and platforms they provide are the result of large continued expenses in research and development, and that this fee is appropriate for the advantages the App Store gives to the developer.

Did you know that Apple charges every developer $100 a year for the ability to submit their apps to the App Store?

Hey

Yesterday, the folks at Bandcamp unveiled a new, paid email service called Hey. They submitted it to the App Store before launch, and the app went live alongside their service (at least I presume Monday was their intended launch day. Many developers know all too well that an App Store rejection can ruin a launch, and sometimes being on time is a small miracle). Bandcamp's developers immediately found a few small bugs they wanted to fix, so they pushed 1.0.1 to the App Store, but it was denied.

The reason? App Store rule 3.1.1:

If you want to unlock features or functionality within your app, (by way of example: subscriptions, in-game currencies, game levels, access to premium content, or unlocking a full version), you must use in-app purchase. Apps may not use their own mechanisms to unlock content or functionality, such as license keys, augmented reality markers, QR codes, etc. Apps and their metadata may not include buttons, external links, or other calls to action that direct customers to purchasing mechanisms other than in-app purchase.

Hey's developers were puzzled, and rightly so, because their app did not feature in-app purchases. Similar to its parent product, Basecamp, the app was only for users who had paid for the service on the internet, it did not allow sign ups in-app and did not feature any in-app purchases.

Apple called Hey, and explained that they were required to allow users to purchase their service in-app to use the App Store, and that their initial acceptance of the app was in error. They must now choose to either give Apple 15-30% (there is a sliding scale for in-app purchase commissions) for sign-ups on iOS, or not be accessible on iOS, watchOS, and iPadOS at all.

I can't imagine anyone reads this and doesn't find it egregious, but what is even more staggering, is that Apple is so committed to this stance on developer relations that it is willing to forego its public image to enforce it. Per David Pierce's excellent piece:

Apple told me that its actual mistake was approving the app in the first place, when it didn't conform to its guidelines. Apple allows these kinds of client apps — where you can't sign up, only sign in — for business services but not consumer products. That's why Basecamp, which companies typically pay for, is allowed on the App Store when Hey, which users pay for, isn't. Anyone who purchased Hey from elsewhere could access it on iOS as usual, the company said, but the app must have a way for users to sign up and pay through Apple's infrastructure. That's how Apple supports and pays for its work on the platform.

Bandcamp's CTO David Heinemeier Hansson had an excellent thread about this decision on Twitter, and its relation to the EU announcement. I recommend reading the whole thing.

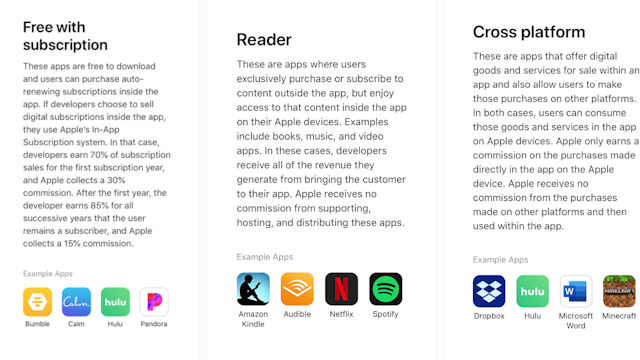

Apps like Netflix do not offer in app signups and Apple says they are not required to because they are 'reader apps'. There are other paid email apps in the App Store like Spark that offer premium plans outside the App Store but not through the app.

Speaking of video apps…

The Amazon Deal

Apple seem to only care about enforcing these rules when it is advantageous to them.

For years, iOS users were unable to purchase or rent content in Amazon's Prime Video app because Amazon didn't want to give Apple a cut. Then, in April, this changed - not only were you able to buy content in the app, but you could do it using Amazon's 'Apple-tax'-free payment system.

How could they get away with this you may ask? Well, Apple told Boomberg's Mark Gurman that, all of a sudden, it has a special 'partner' program for video services, allowing them to seemingly bypass the App Store's taxes in exchange for utilizing Apple's services (integration with Siri, Apple TV, etc.)

The members of this program? Canal+, which Apple claimed had been on since 2018, Altice, and Amazon.

Essentially, the 'big dogs' in media and streaming can surpass these stringent rules as long as they give Apple a little something extra in return - while also pleasing consumers by having services they expect to work on their devices. Medium sized businesses and independent developers get no break.

Spotify

Spotify has perhaps been the largest corporation to go against Apple's App Store policies publicly. They've even made an entire site complaining about it.

I disagree with some of Spotify's complaints, and feel they detract from the overall importance of their speaking out. There's a major difference between overtaxing complaints and technical constraints of Siri and the Apple Watch. Whether or not Apple could've hypothetically enabled an Apple Music like Spotify experience on the Apple Watch earlier or was being anti-competitive is hard to litigate, though it's platform practices certainly show anti-competitive behavior.

Spotify has two very good complaints. Their first complaint is the one we've been addressing so far: Apple takes 15-30% while not allowing them to use their own payment gateways, and if they stop they will not be allowed on the App Store at all. Music Streaming is ostensibly a duopoly, and Spotify is in a particularly unforgiving situation because their main competitor is insisting on taxing their platform.

But this leads to Spotify's second issue - that because Apple controls the iPhone and Apple Music, they are not only being taxed needlessly, but are also already at a dramatic disadvantage due to the pre-installation of the Music app on every iPhone.

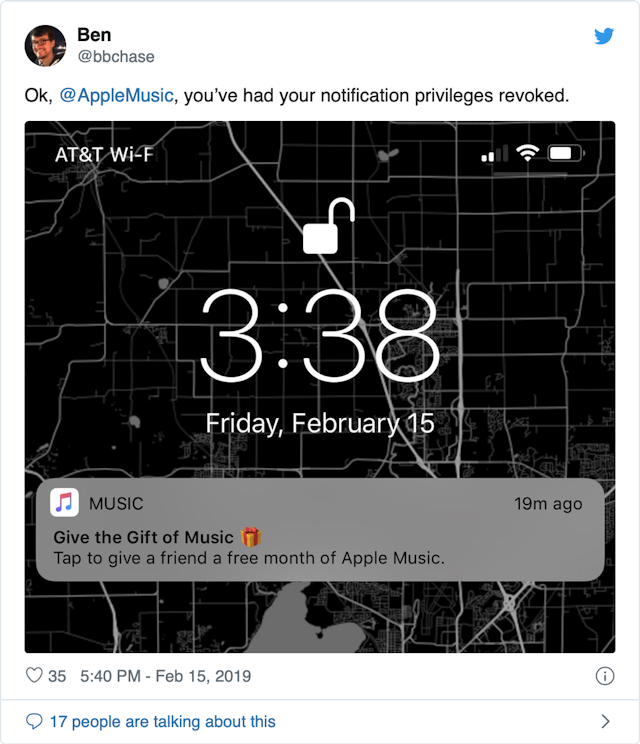

And, not only does Apple not have to pay a tax or get users to install their app, they actively break their own rules by using non-compliant push notifications:

Push Notifications should not be used for promotions or direct marketing purposes unless customers have explicitly opted in to receive them via consent language displayed in your app’s UI, and you provide a method in your app for a user to opt out from receiving such messages. Abuse of these services may result in revocation of your privileges.

Apple's Spotify Response

After Spotify put Apple on blast, Apple created a website that attempted to explain the App Store policies. A couple interesting tidbits I want to put here:

This is the clearest explanation I can find for the 'reader' type apps that Apple said Hey was not. "These are apps where users exclusively purchase or subscribe to content outside the app". In what way does this not apply to Hey? It certainly does not fall into 'Free with Subscription', as there is no free tier. Apps that are 'cross platform' are defined by whether or not they offer digital services for sale within the app as well as other platforms - this reads like a definition, not a requirement. If the intention of this section is to say 'if an app isn't a book, music, or video, they must offer in-app purchases', this is an incredibly deceitful illustration of that rule.

The funniest part is later on though:

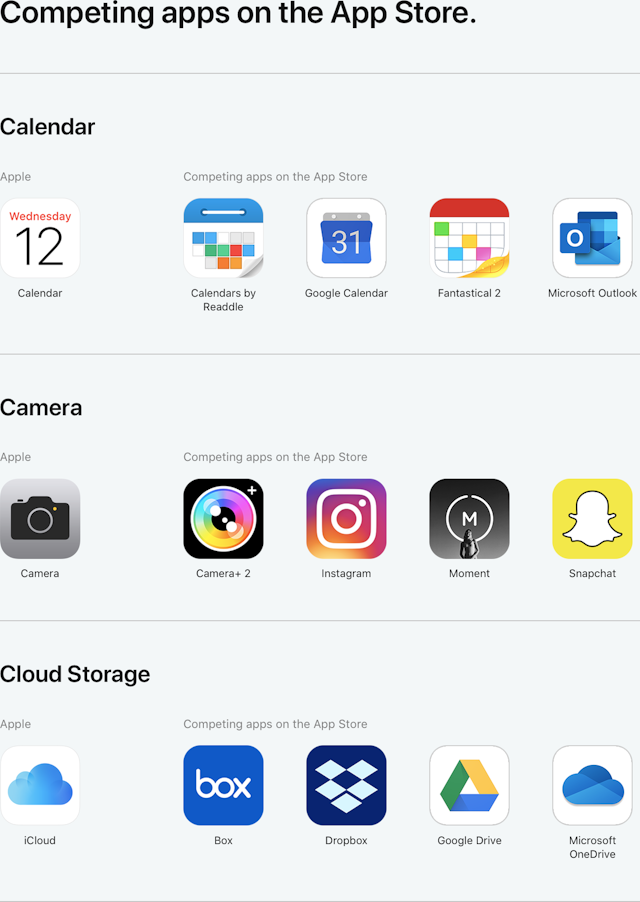

Apple attempts to argue that the App Store is not anti-competitive because of all the similar apps on the App Store to its own services, without truly addressing the problem. Imagine if Microsoft showed this slide during their anti-trust lawsuit in 2001:

So just in case Apple still doesn't get the point, I'll say it again:

The problem is not whether you have competitors, it is whether you are putting your competitors at an unfair disadvantage. You can not change your default apps on iOS, and practically all these services come pre-installed on the iPhone, which is the singular most popular device in history. Lastly, if you're going to have rules and call these apps your competitors, it is inherently anticompetitive to break them (see Apple Music, Apple TV+ and Apple News spam notifications).

If Apple doesn't want to lose the App Store, I'd become less developer hostile very quickly.

Valve

I briefly mentioned before that Apple's unclear and unfair App Store rules can sometimes ruin a launch. I've personally had this experience when I was launching Aerate last year, which I had to delay due to Apple's continued rejection for breaking some obscure rule, despite having submitted the release build about two weeks before launch. (In the end, we were not using the correct type of in-app purchase, but this was never clearly explained to us)

In order to illustrate how big a problem this is though, I'm going to use a larger example to show that Apple not only ruins independent developer's launch plans with unclear rules, but even does large corporations.

In May 2018, video game publisher and distributor Valve planned to release Steam Link, a remote desktop application that allowed users to access their game library on their iOS device. Apple approved the update on May 7, and on May 9, Steam published the app and announced its launch.

However, as soon as they announced it, Apple pulled the app, citing 'business conflicts with app guidelines'…

I'll just leave that one there for open interpretation.

Following the story, Apple revised its policies the next week to allow the app in the App Store. And while Valve has the resources and name to push change when it's needed, independent developers do not. They must either comply or get out - and you must play by Apple's rules.

Search Results

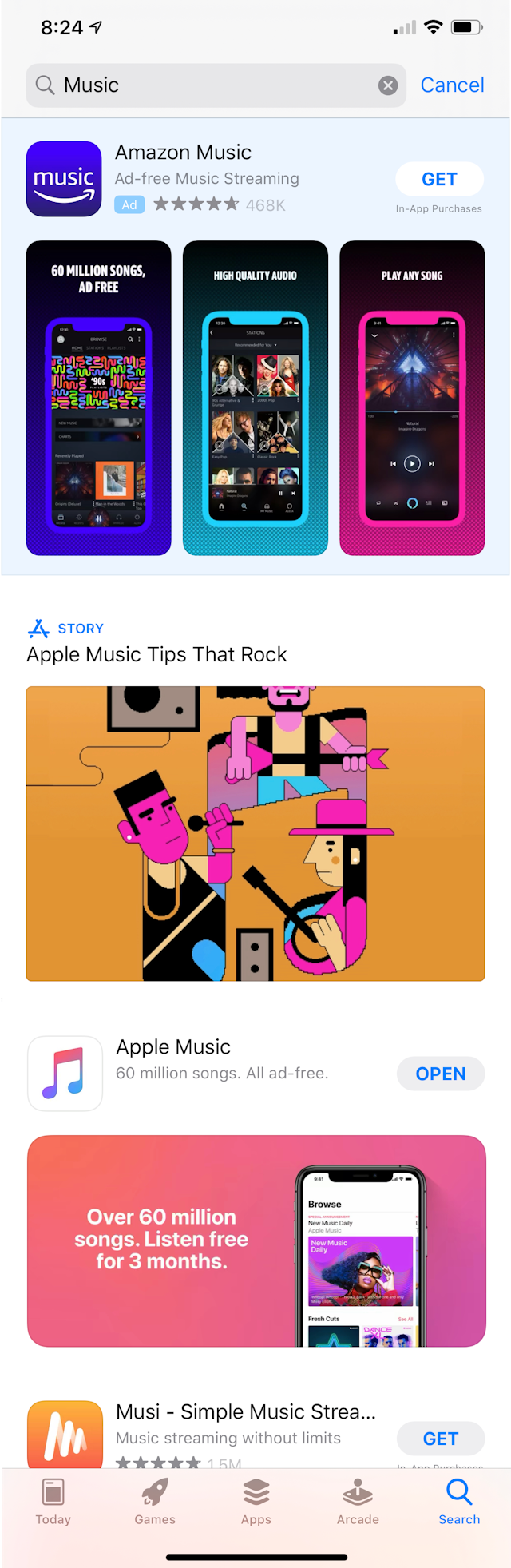

As detailed in a September 2019 New York Times report, Apple's algorithm had been unfairly favoring Apple apps in App Store search results vs. 3rd party apps. Following the report, Apple tweaked the algorithm so things like 'Compass' wouldn't be the 3rd result when you searched for Music - saying that "the algorithm had been working properly. They simply decided to handicap themselves to help other developers."

This report needs a follow up though, because Apple has since tweaked its search practices to be even more developer hostile and anti-competitive.

It appears the change I'm referring to is a result of the introduction of App Store stories, a new feature added a few years ago that showcases apps Apple has deemed interesting on the App Store. It has also decided that it's own apps are very worthy of such attention, and search results favor stories over apps.

Thus, if you search for 'music' right now on the App Store, you will see this:

"Apple Music tips that rock!". The only logical, though still unacceptable explanation, to this problem would be that it's basing it on views, and the story has more views than the app - but it can't possibly be that a story about Music has more views than Music, can it?

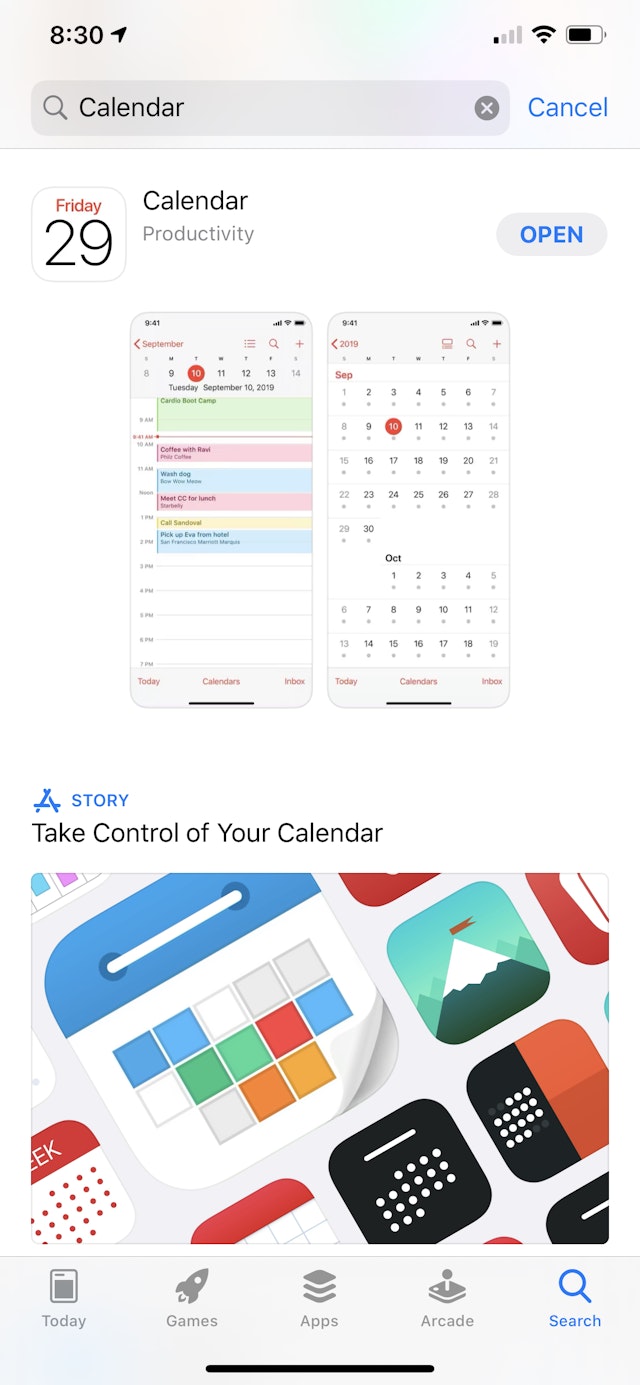

Even worse, when you search 'Calendar', you get the Calendar app first, than a story, and then Apple's competition.

No Apologies

How can developers realistically compete on a platform where the operator is clearly hostile? In all of the example I've shared here, Apple has had no qualms about being openly malicious with large corporations, save for Hey (a small-medium sized corporation). All of these companies were able to deliver their side of the story due to their size and voice, and hopefully, their speaking out will result in seriously needed changes to the App Store monopoly.

As the Worldwide Developer Conference approaches, I ask you to consider this question: Does Apple really care about developers? When they try and undo these most recent nefarious acts, will we forget about it until the next time it happens and wait for some government to force their hand?

It's important to think about the little guys. Independent developers are actively being targeted by Apple due to these practices. I think it is important that we as consumers demand Apple treat its most important partners much better, and if not, perhaps extreme measures as a community need to be taken.